Too Poor to Die

Encountering the Destitute Funeral at The Way Community

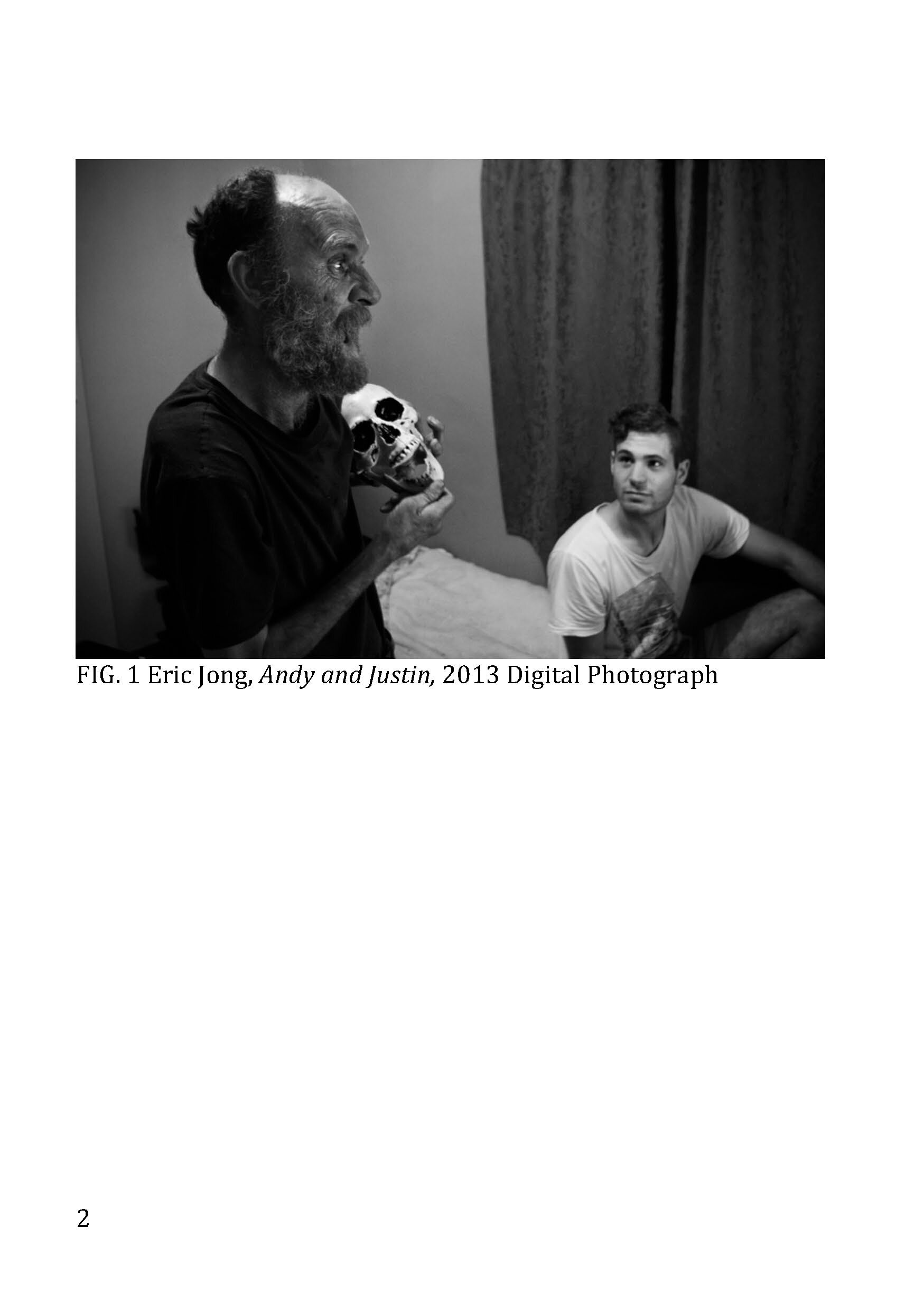

While working as a photojournalist I undertook a longform project with The Way Community, a home to men over the age of forty whom have experienced homelessness and are challenged with severe alcoholism, drug abuse and mental health issues. As part of that project I profiled Justin, a young employee who had been working at the shelter since the age of fifteen. At the time of the interview he had been working at The Way for eight years. We spoke at length about how formative his experiences within such an intense environment were to him as an individual. For Justin it was a steep learning curve that required the balance of his role as a carer, and maintaining a strong emotional guard to mange the toll.

There was only one occasion over the course of our time together that Justin dropped that guard, breaking into tears. It was when I asked him about what happened when residents of The Way eventually died.

“It’s sort of the last stop on the end of a long train ride. And you know, it’s not a pretty end but it’s a quiet and nice one. And they sort of, its sort of like the fade into black at the end of a movie. You know, pausing for thought.

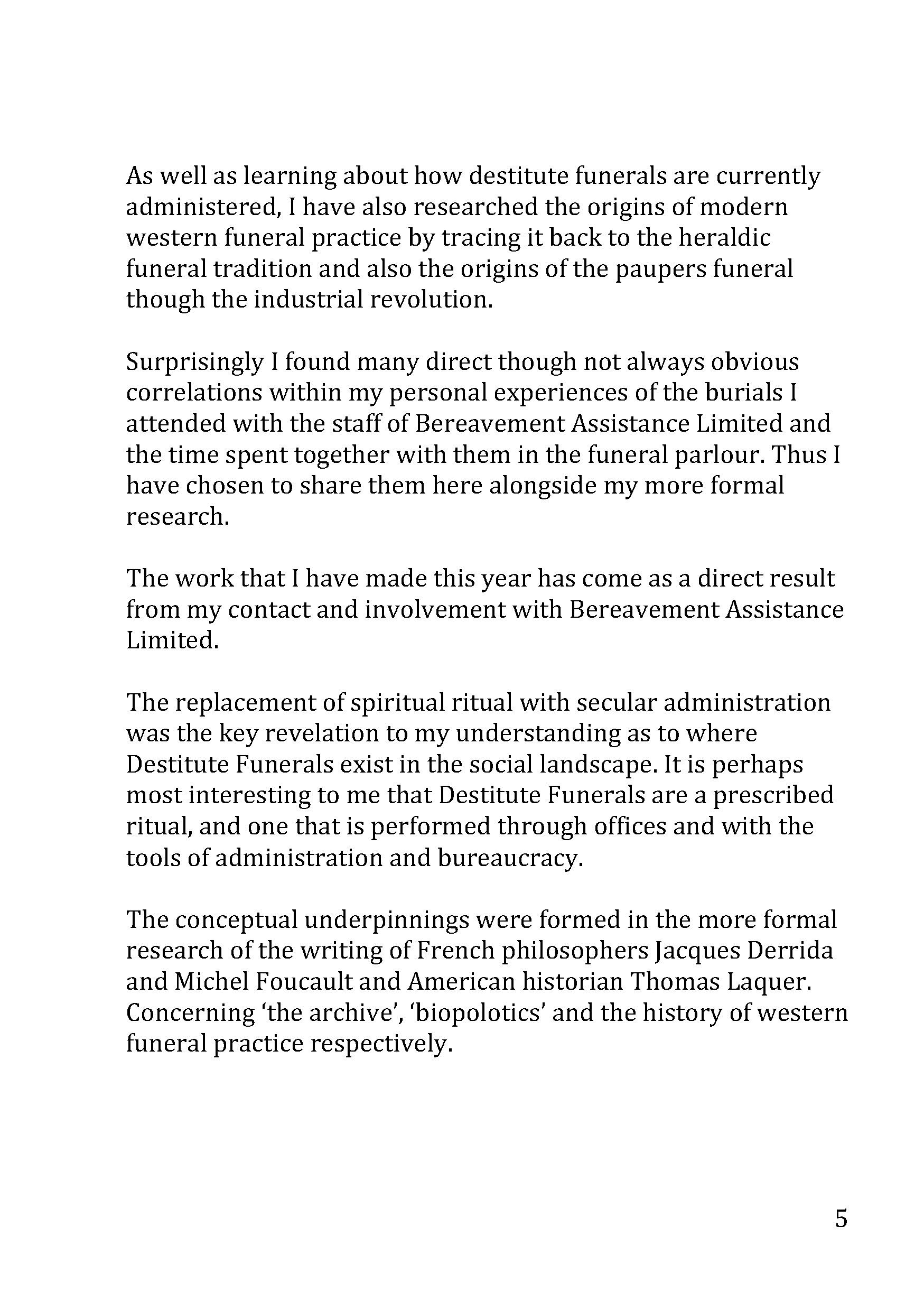

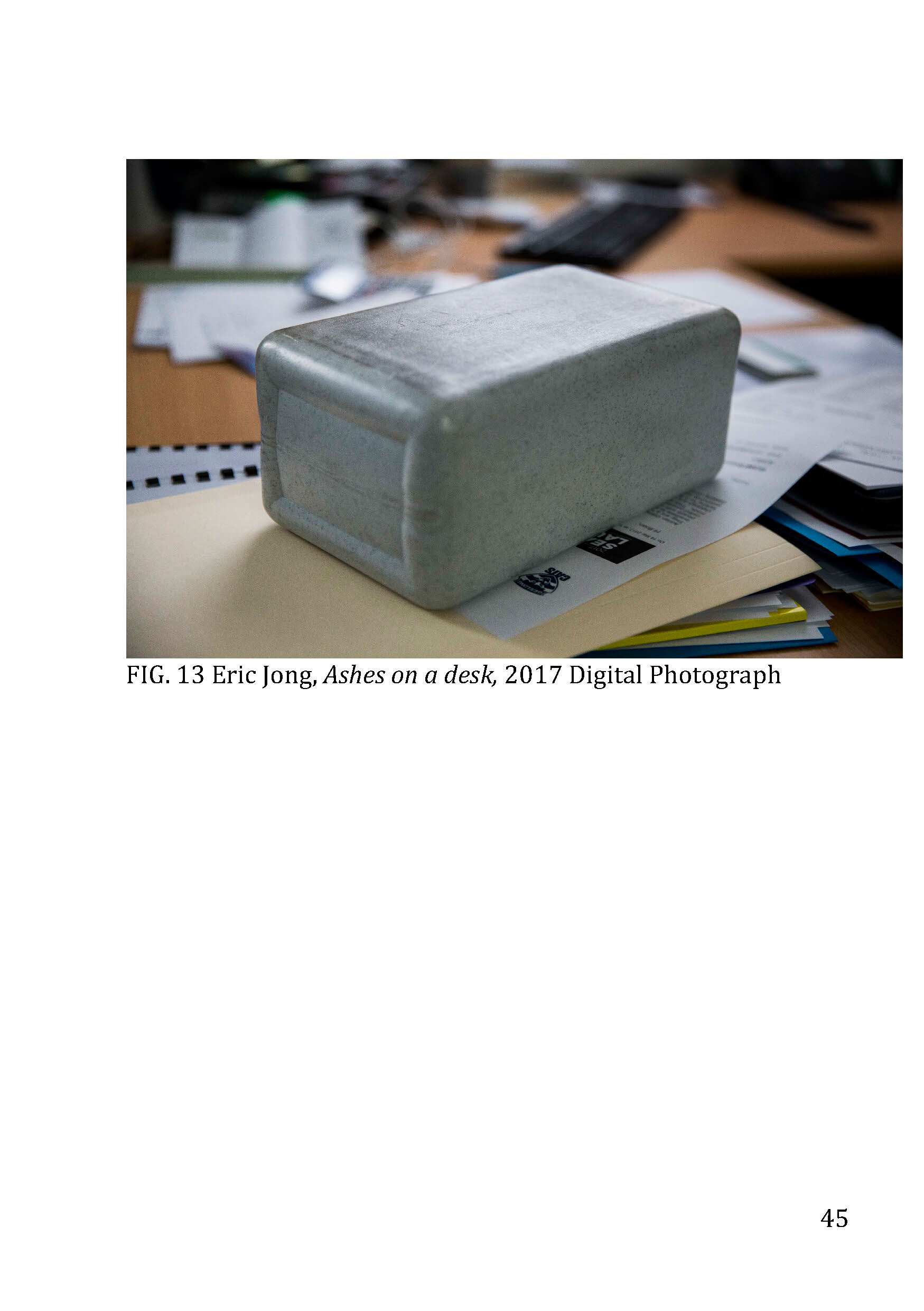

So these men, they come here, they’re already ruined. You know? And it’s just the final scenes playing out. And, even when they do die, when they end up getting buried or whatever, a lot of the time the family doesn’t want to have anything to do with them. And we end up with their ashes or having to bury them.

There’s a good friend of mine who I took care of at The Way, uhh, Michael. And um there’s a couple of boxes upstairs. Three ashes I think. And I always wonder, like you know. Is my mate Michael in one of those boxes?”

I was later to discover that after a set period of time the boxes would be emptied into the small communal garden on the premises. A garden that the residents would often tend quietly in the afternoons.

Bereavement Assistance Limited

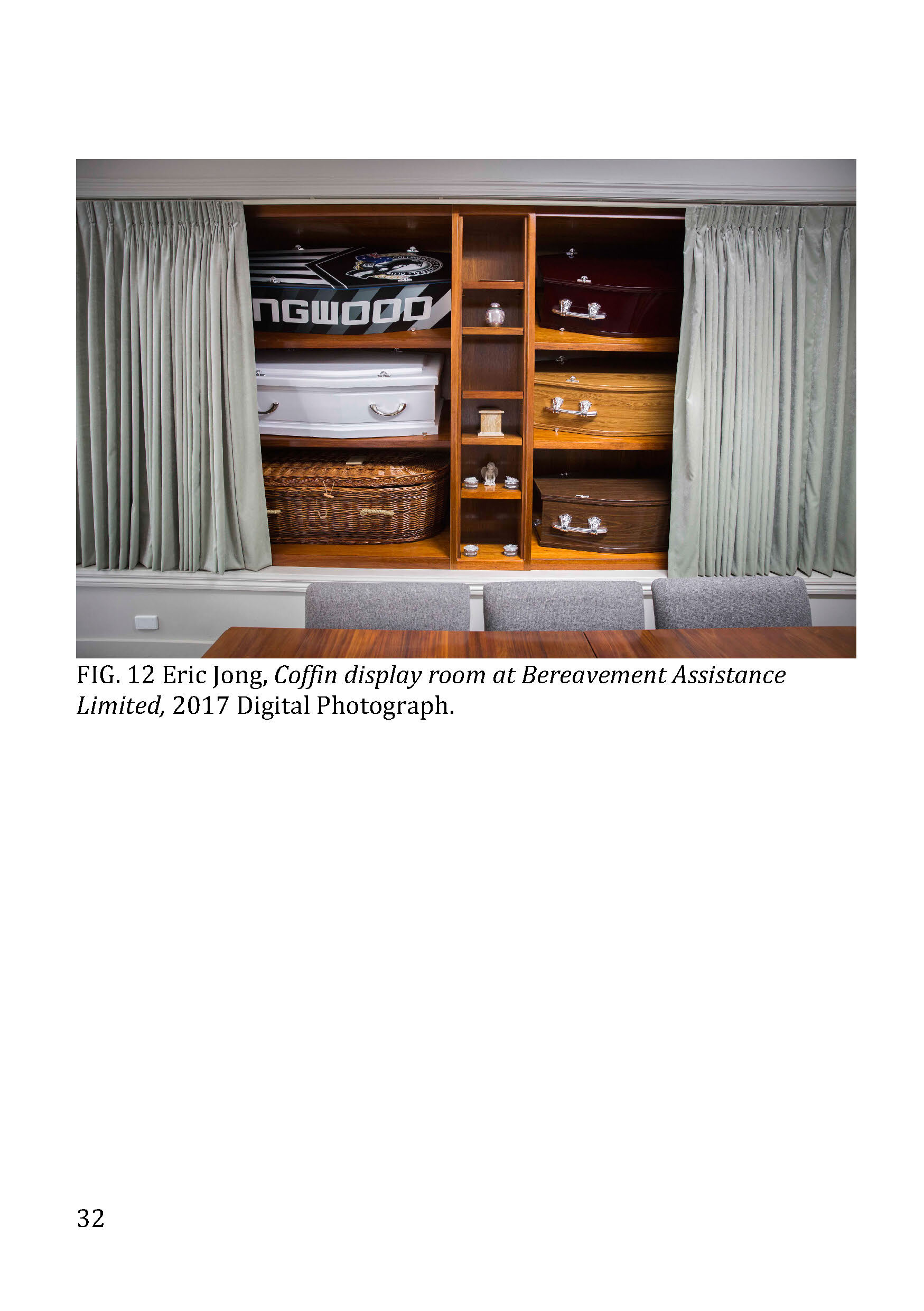

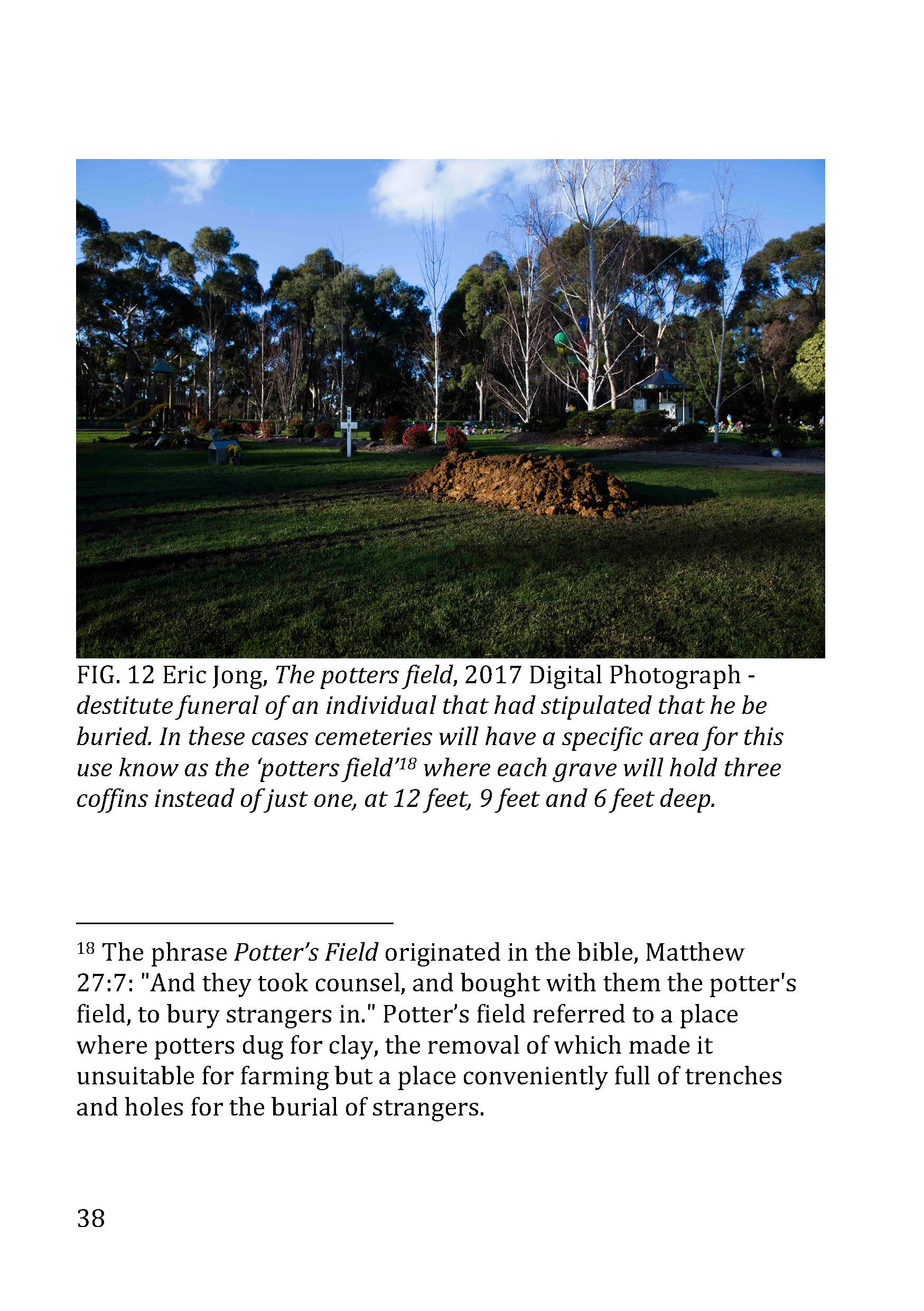

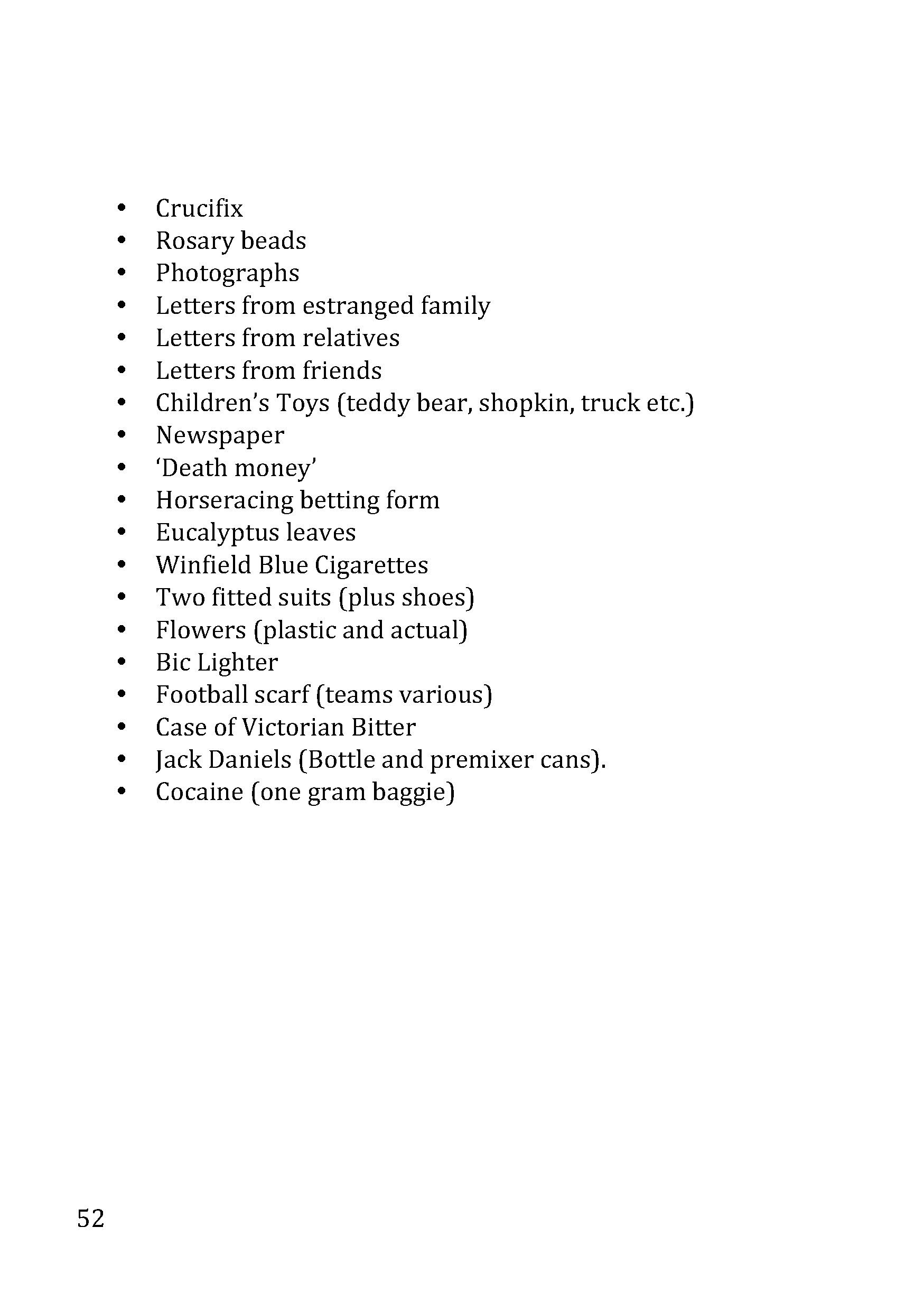

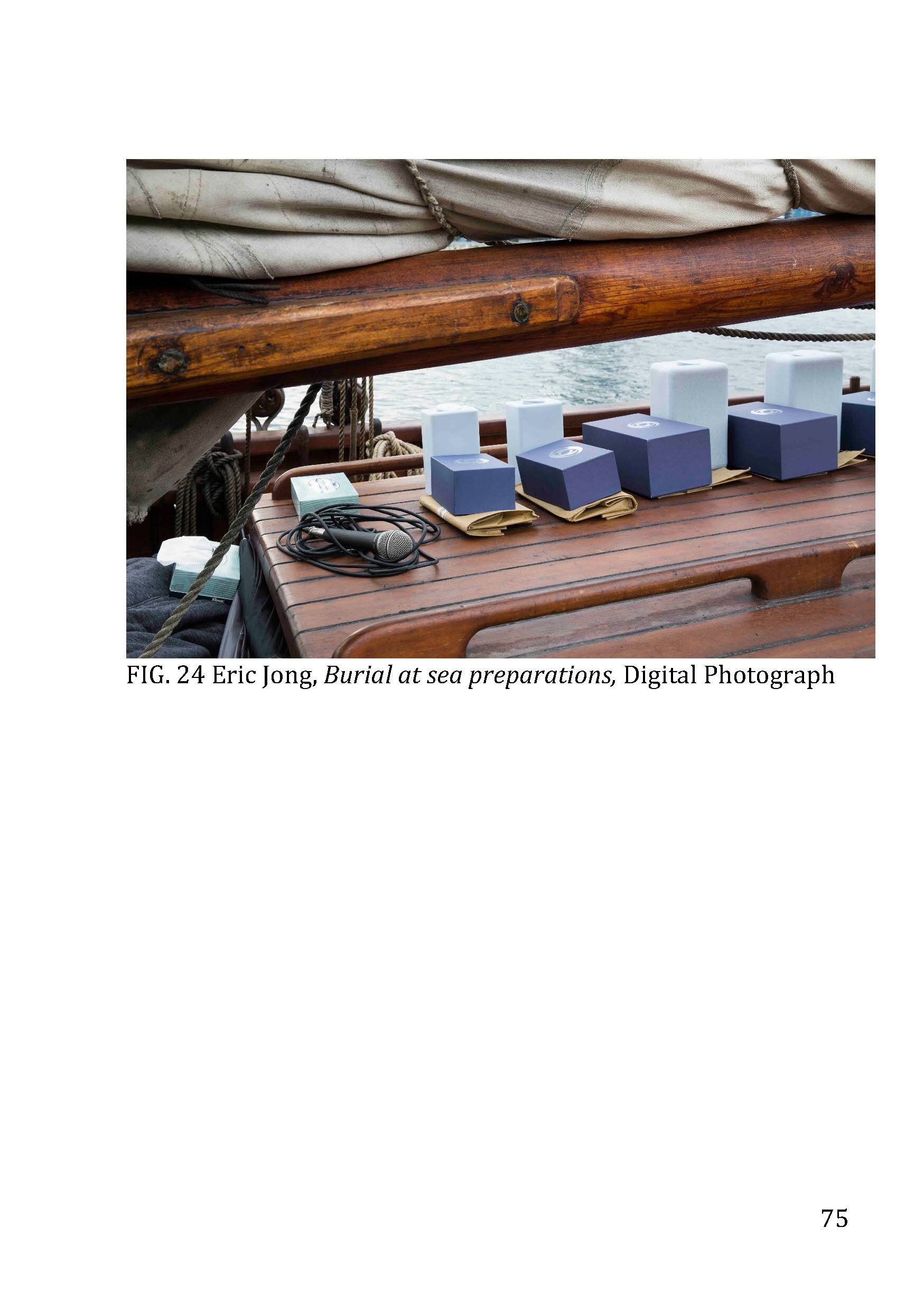

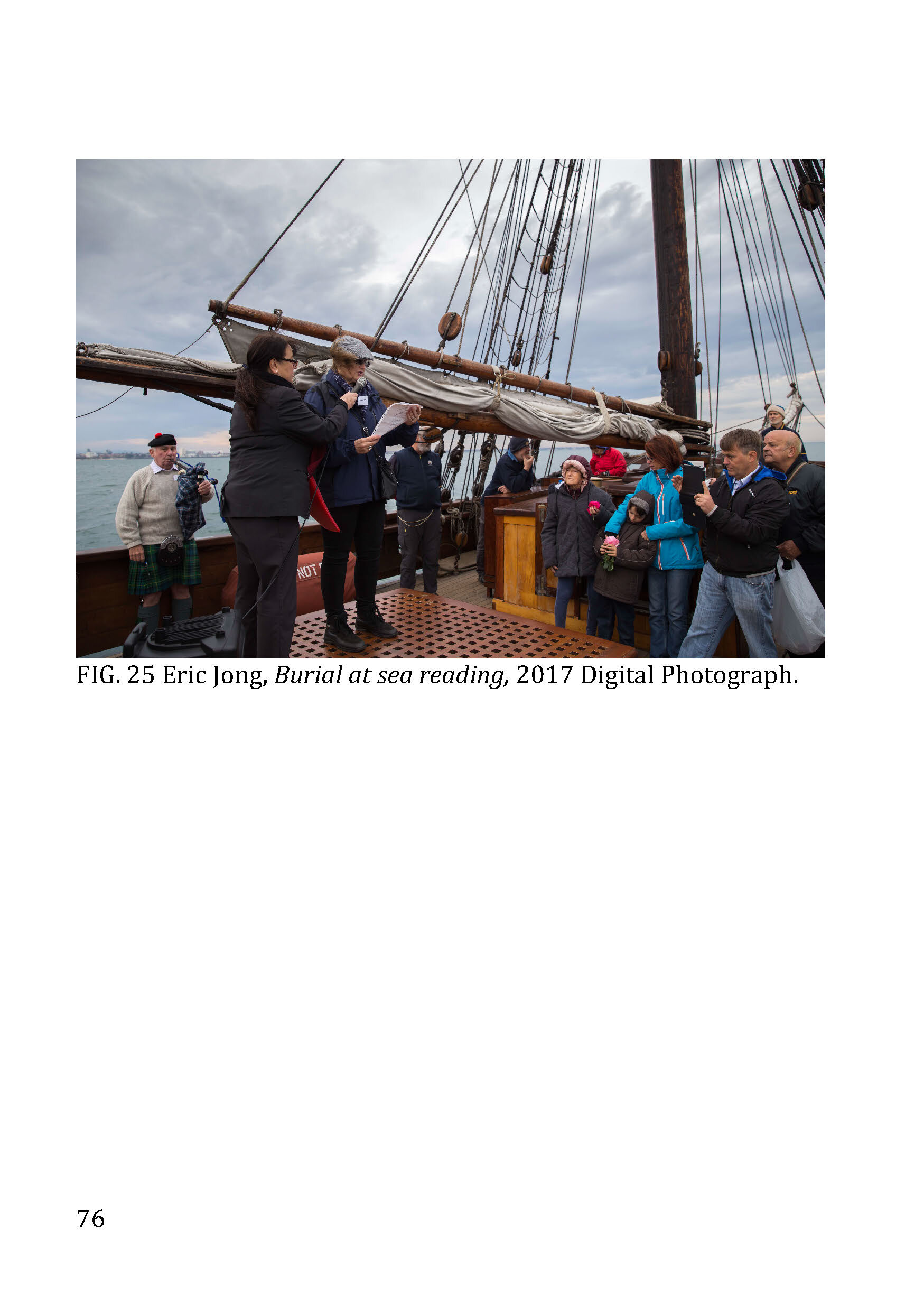

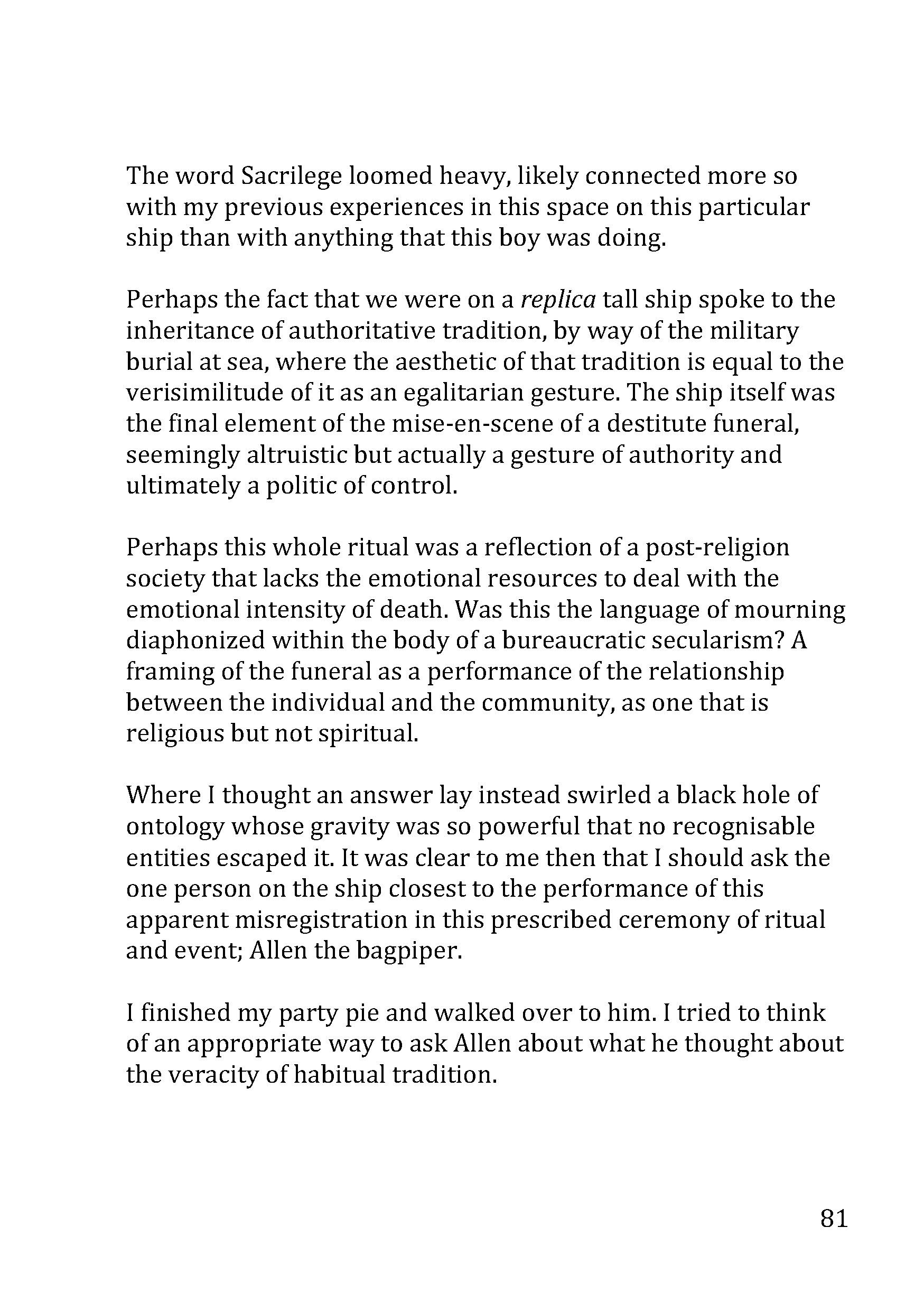

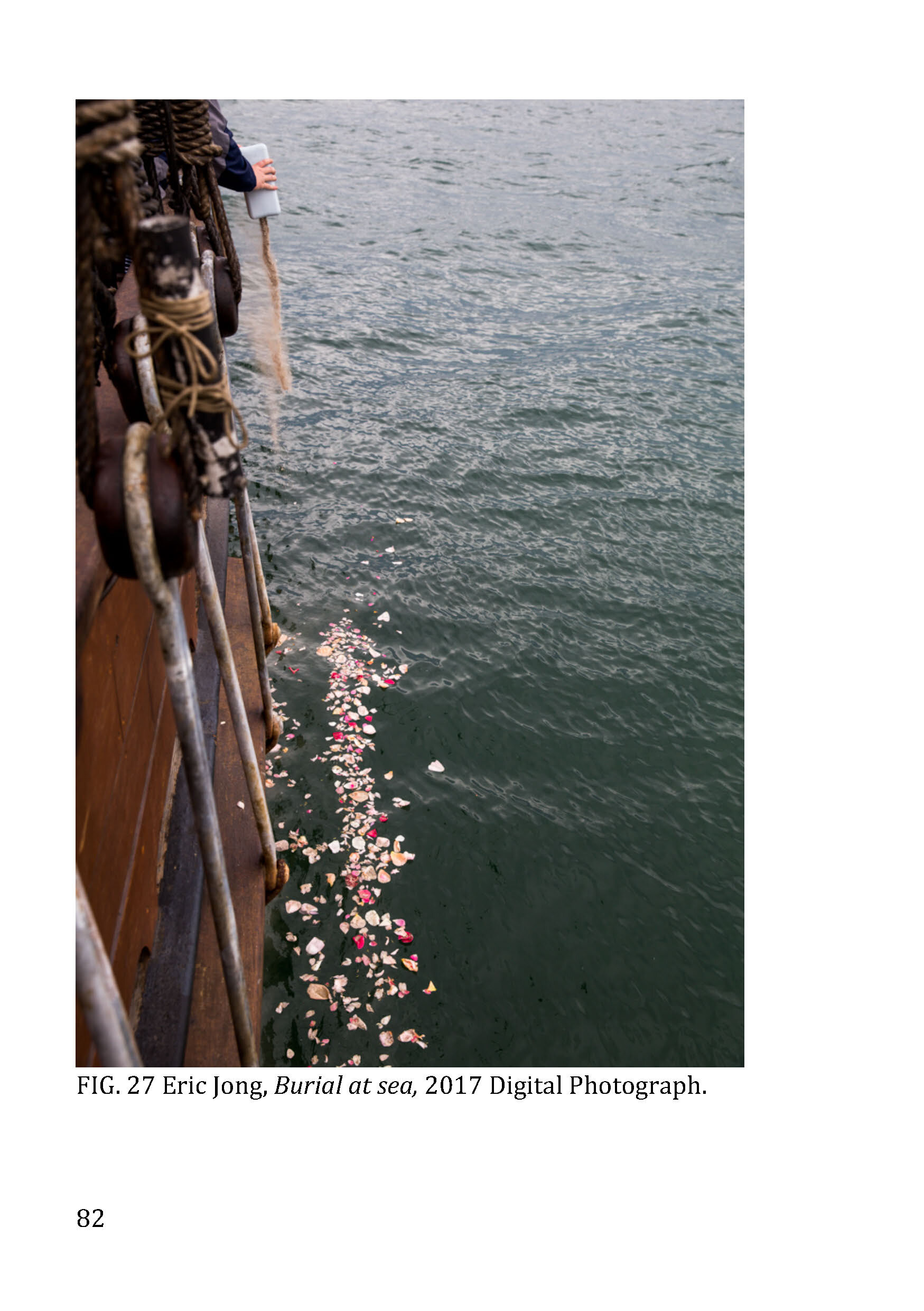

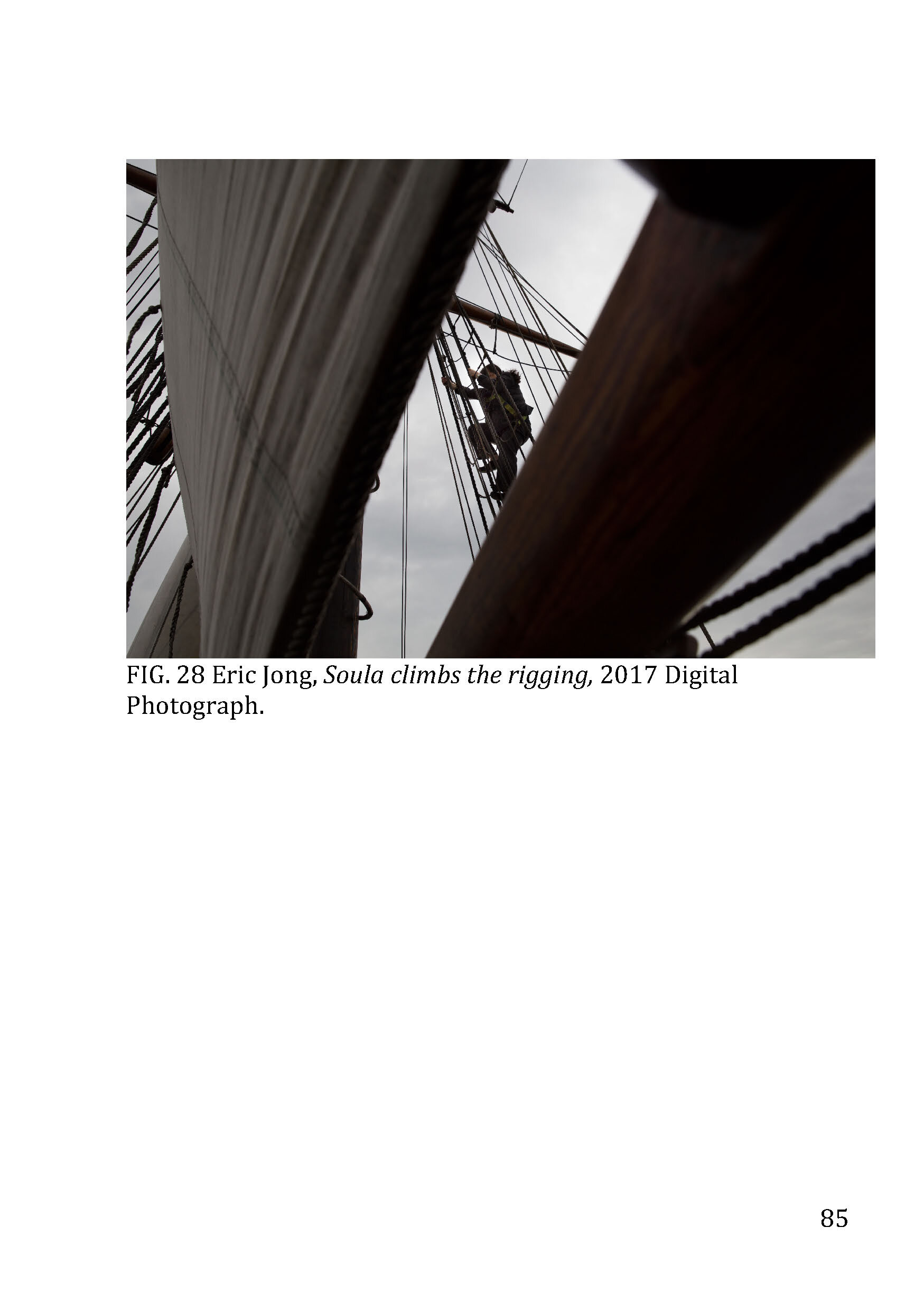

After my first encounter with the destitute funeral the primary source of my research in this endeavour was the time that I spent with the staff at Bereavement Assistance Limited, a funeral parlor that specialises in delivering destitute funerals. They were extremely generous with their time and I was able to spend time with the staff there from whom I learnt the processes, administration and culture of destitute funeral practice, attended a number of funerals including a multiple burial at sea and a burial in a potters field.

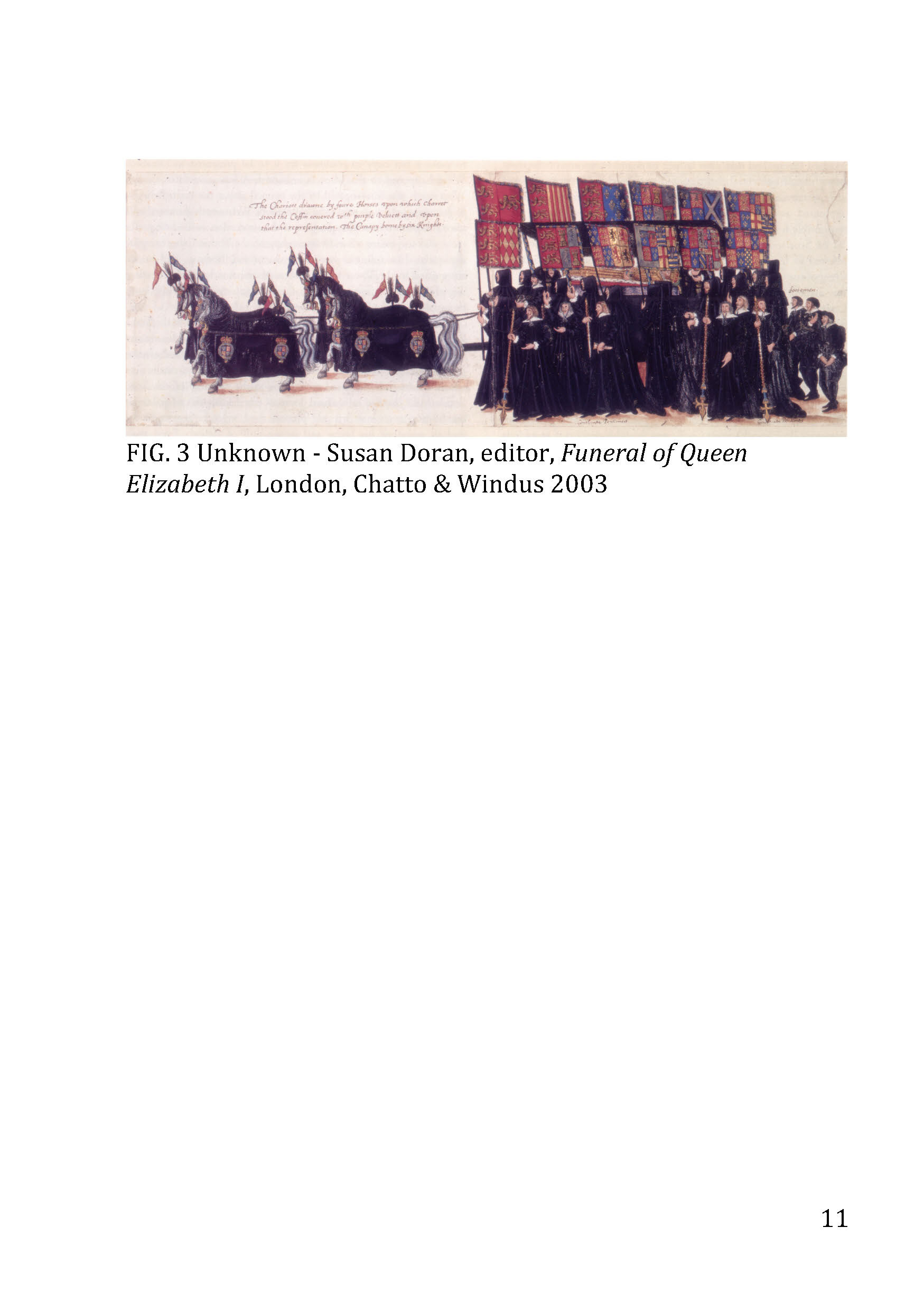

As well as learning about how destitute funerals are currently administered, I was also researching the origins of modern western funeral practice by tracing it back to the heraldic funeral tradition and also the origins of the paupers funeral though the industrial revolution.

Surprisingly I found many direct, though not always obvious, correlations within my personal experiences of both the burials I attended with the staff of Bereavement Assistance Limited and the time spent together with them in the funeral parlour.

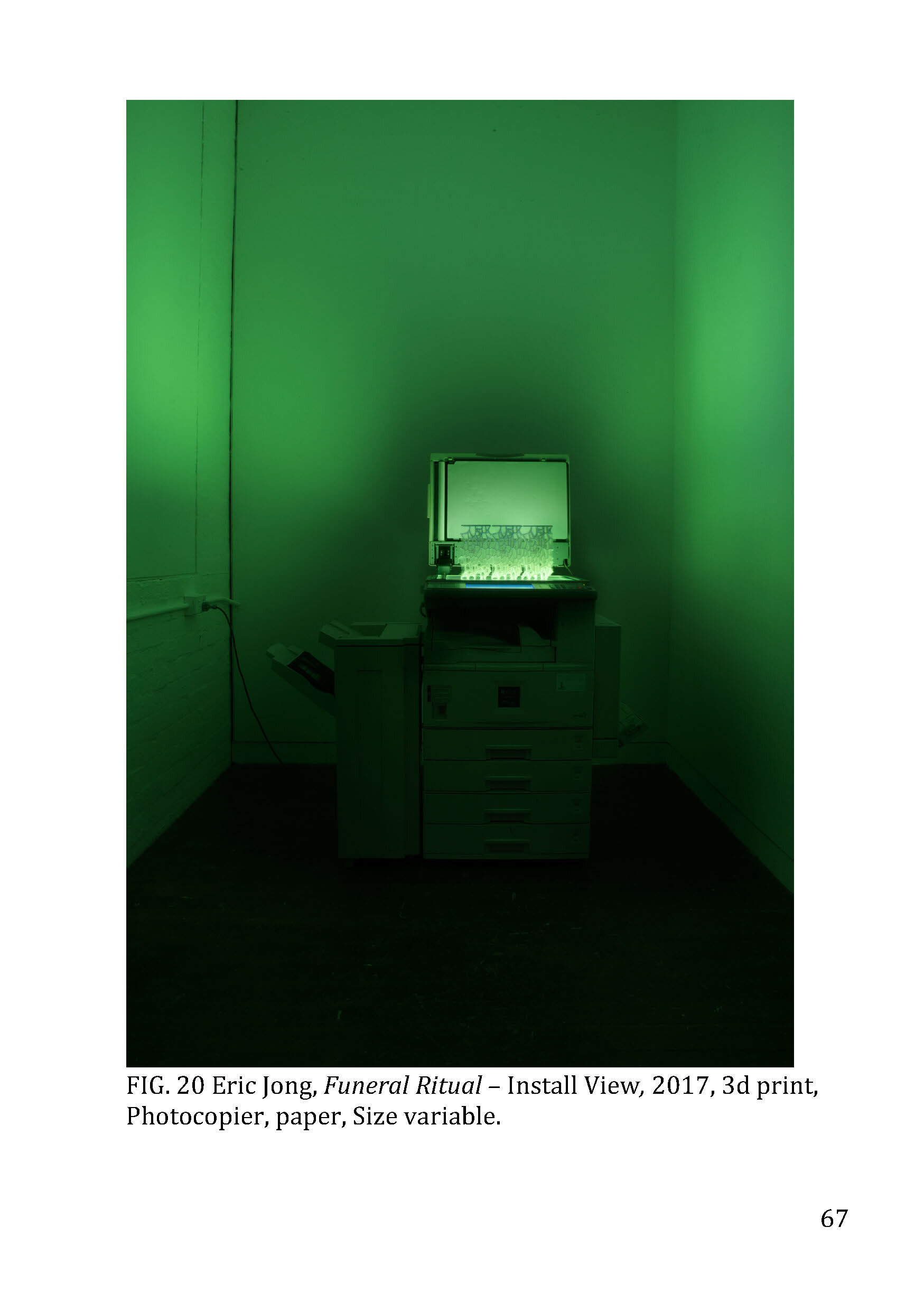

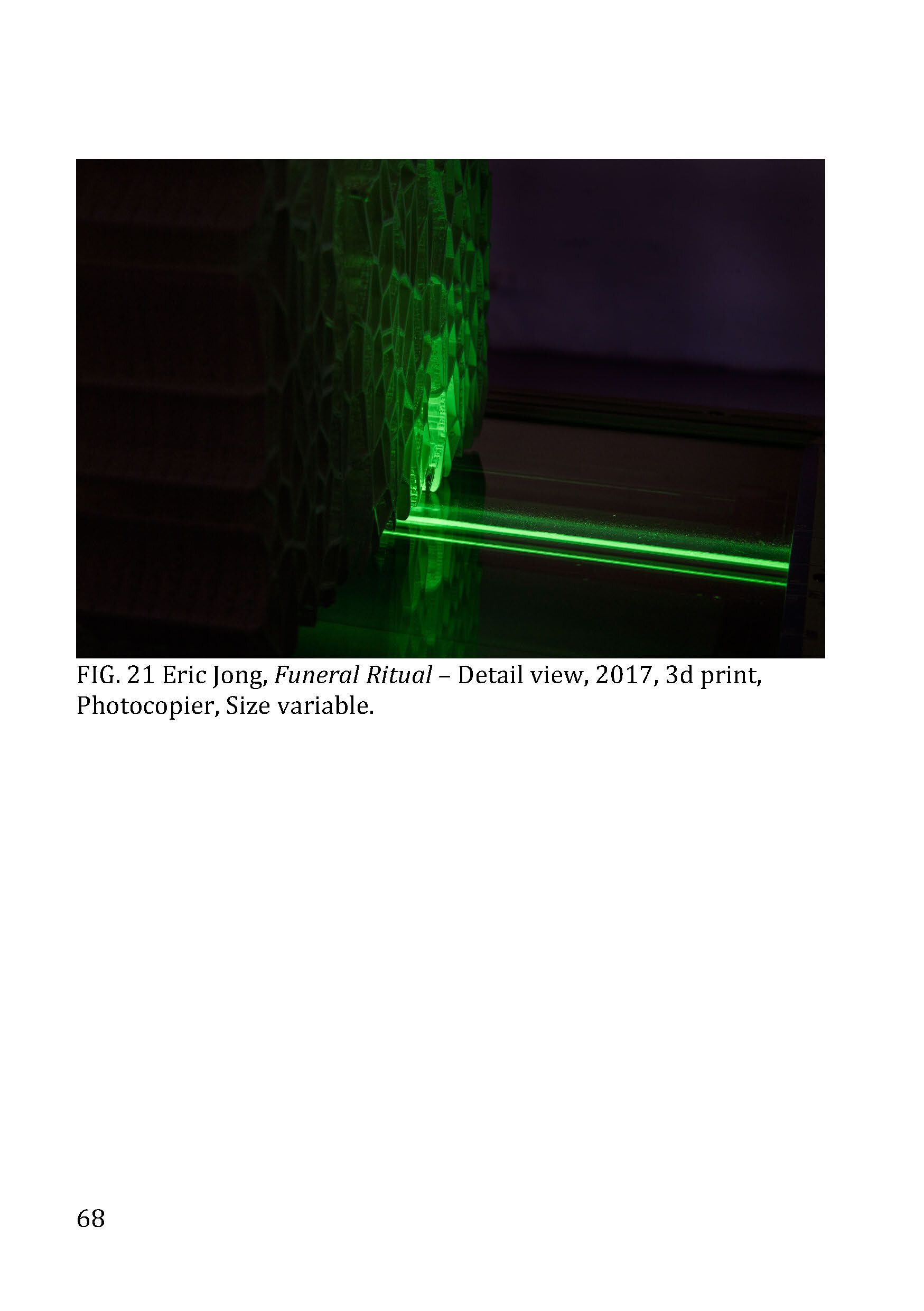

The replacement of spiritual ritual with secular administration was the key revelation to my understanding as to where Destitute Funerals exist in the social landscape. It is perhaps most interesting to me that Destitute Funerals are a prescribed ritual, and one that is performed through offices and with the tools of administration and bureaucracy.

Researching the Destitute Funeral at the Victorian College of the Arts, Honors of Fine Art program

Undertaking the Bachelor of Arts, Honors course at the Victorian College of Arts, Melbourne Univiersity, I was able to make a deep dive in my research. Through the funerals of persons who die without leaving behind personal social connections I began investigating why ceremony and end of life rituals are important to society, and how the treatment of vulnerable persons through them reflects upon our community. Too Poor to Die explores what can we say about our society when we examine the moment that an individual has died alone, and when their identity is completely formed by others and their legacy is canonised through a funeral that is chosen for them.

The destitute funeral has been a common feature of the life-cycle of the poor throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and is well documented through popular fiction and legal tradition. The modern legal responsibility of the burial of the destitute dead has direct roots in the laws of England, which dictated governmental obligation for those who died within their own institutions. The reasoning for this mandatory obligation centres on a societal pressure for religious burial, health and sanitation requirements and dignity of the dead.

The role of the destitute in government institutions has a dual history, with the government acknowledging a responsibility for basic needs, while resenting the undeserving poor, those who were seen to have brought poverty upon themselves The common occurrence in England in the 1800s of grave robbery of the public hospital dead and subsequent medical dissection of the bodies was symbolic of the acknowledgement of the government to take responsibility to provide basic medical care to the poor, while asserting ownership over the bodies after death. There is a element violence embedded in capitalisms construction of victory though competition. A violence that is perhaps felt most intensely after the death of the impoverished through the paupers funeral.

Too Poor to Die explores what can we say about our society when we examine the moment that an individual has died alone, and when their identity is completely formed by others and their legacy is canonised through a funeral that is chosen for them.

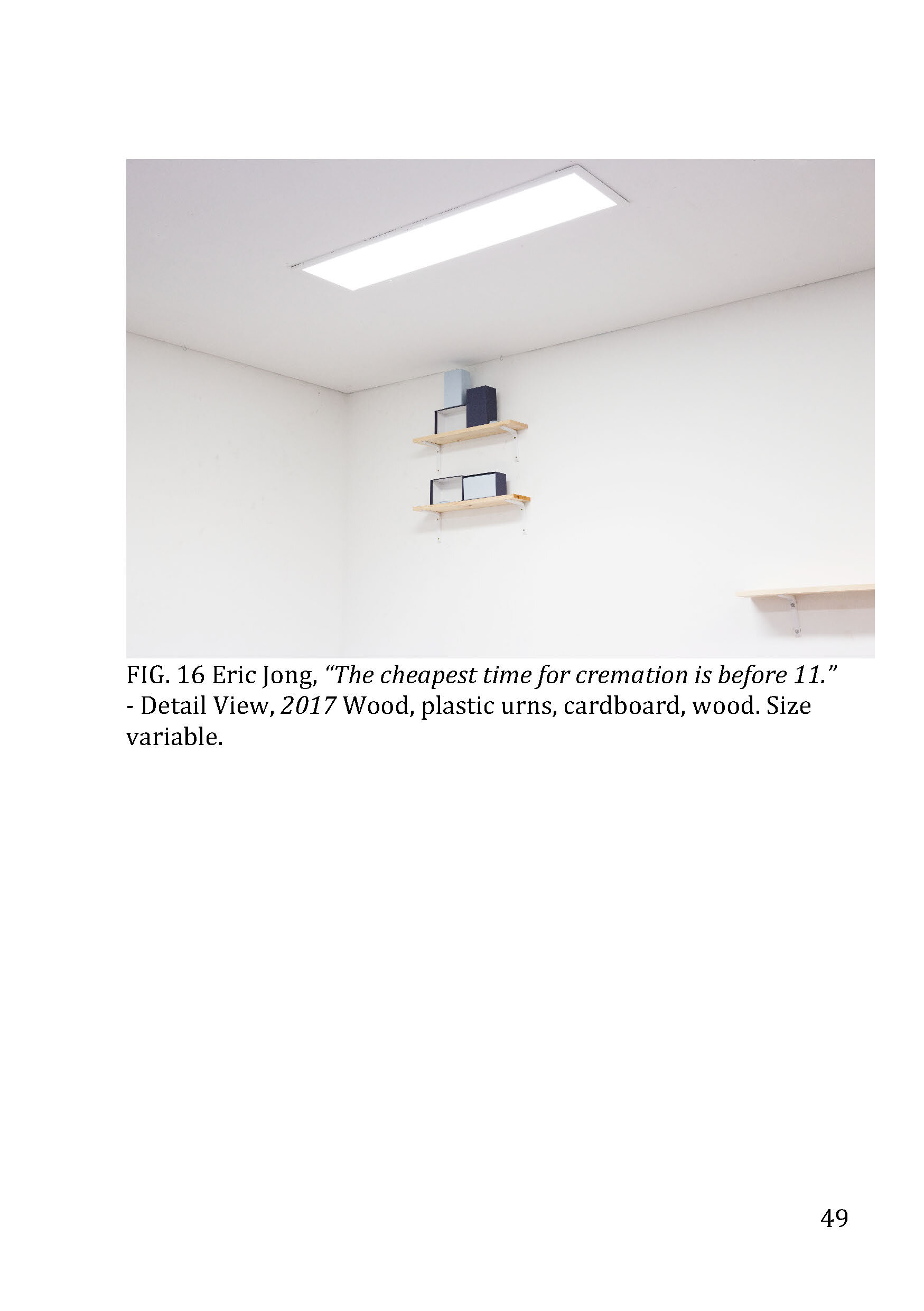

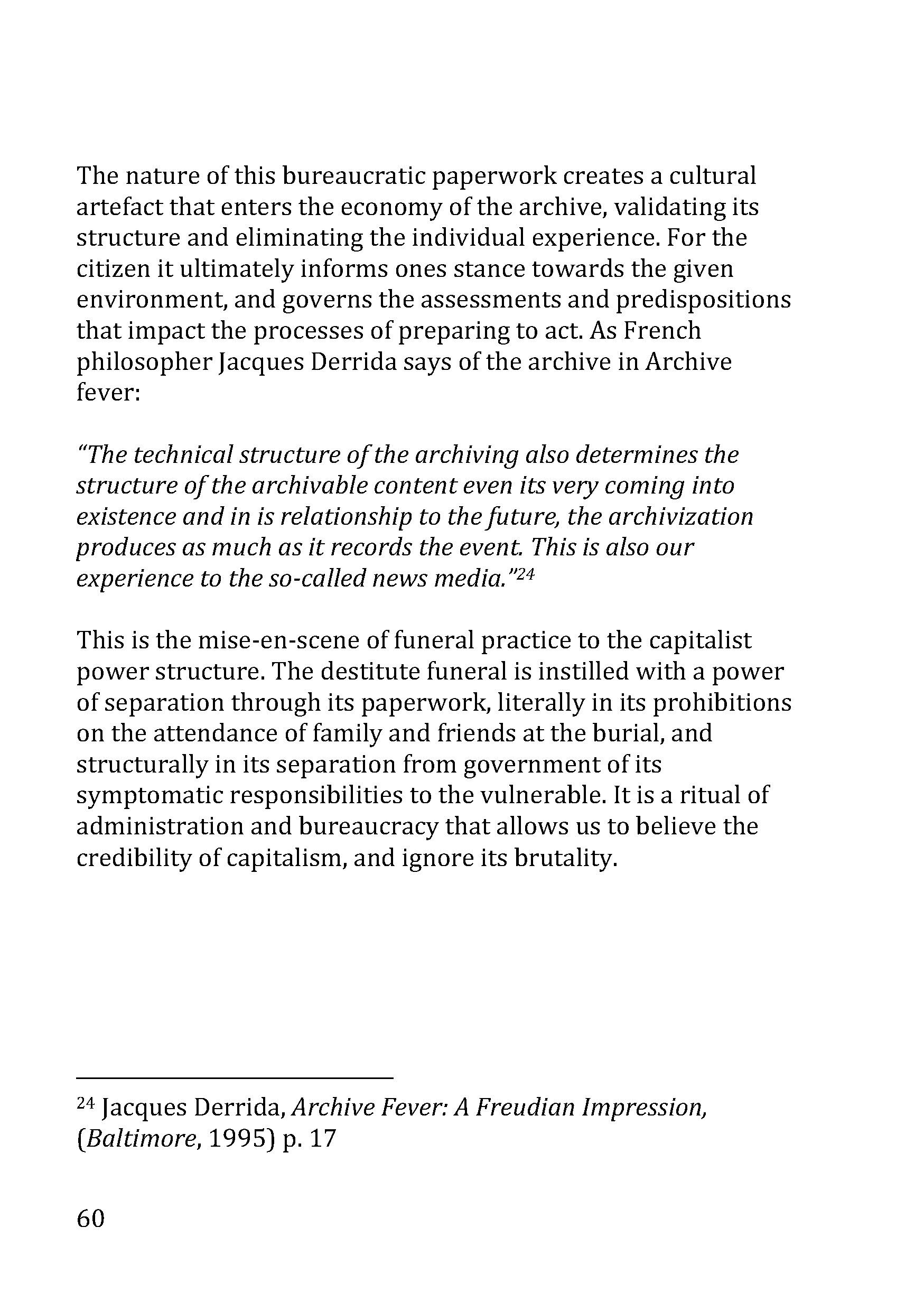

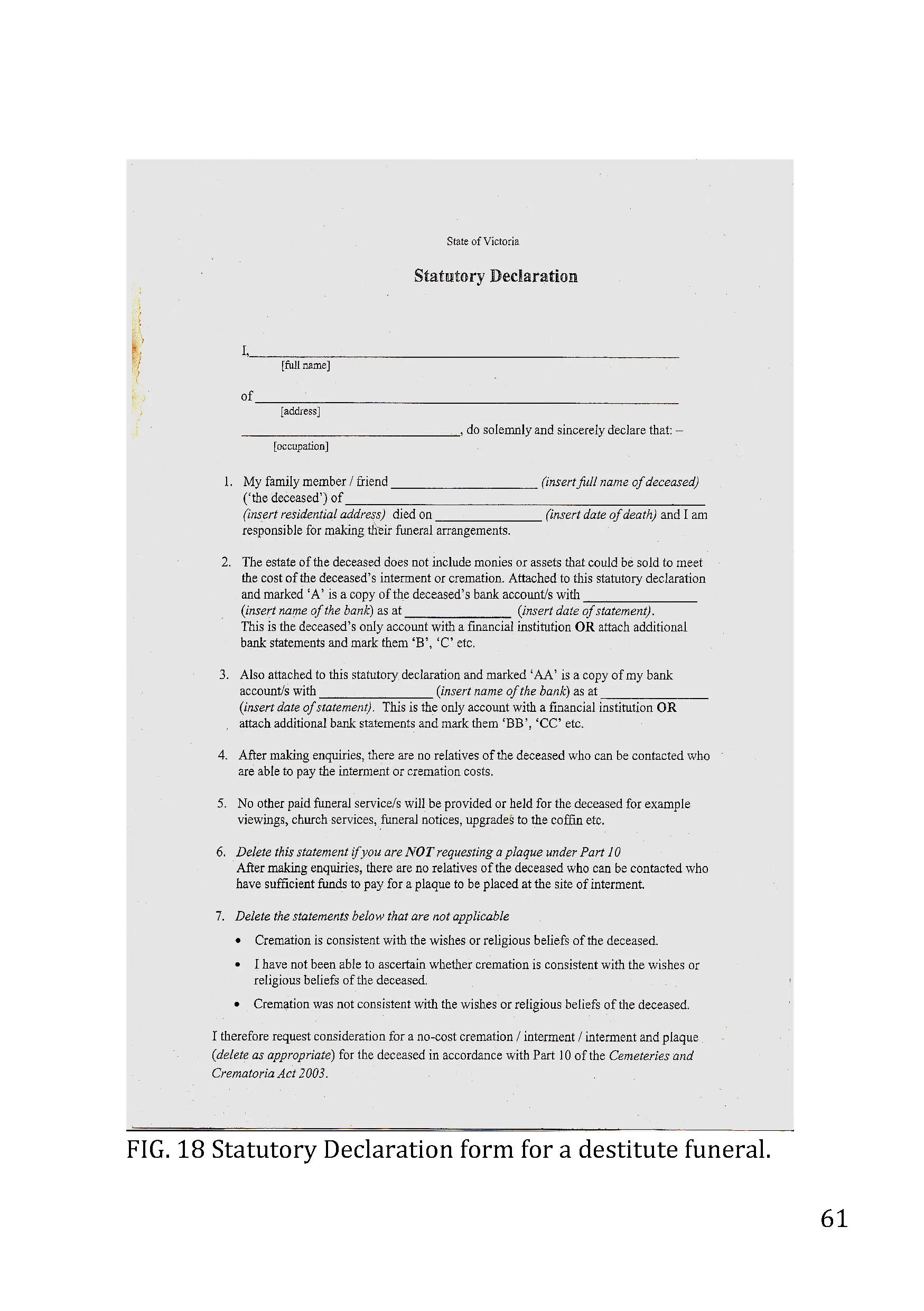

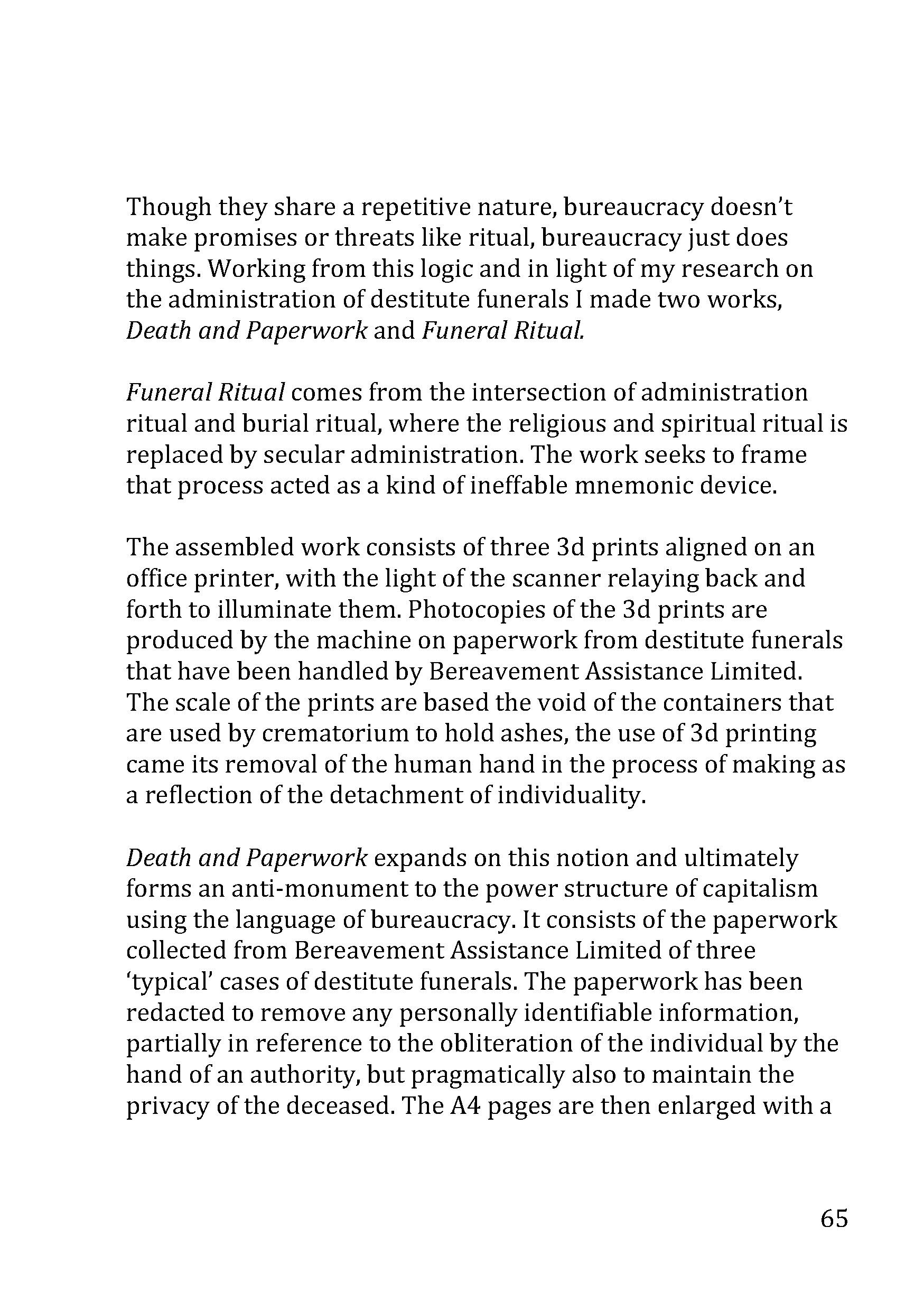

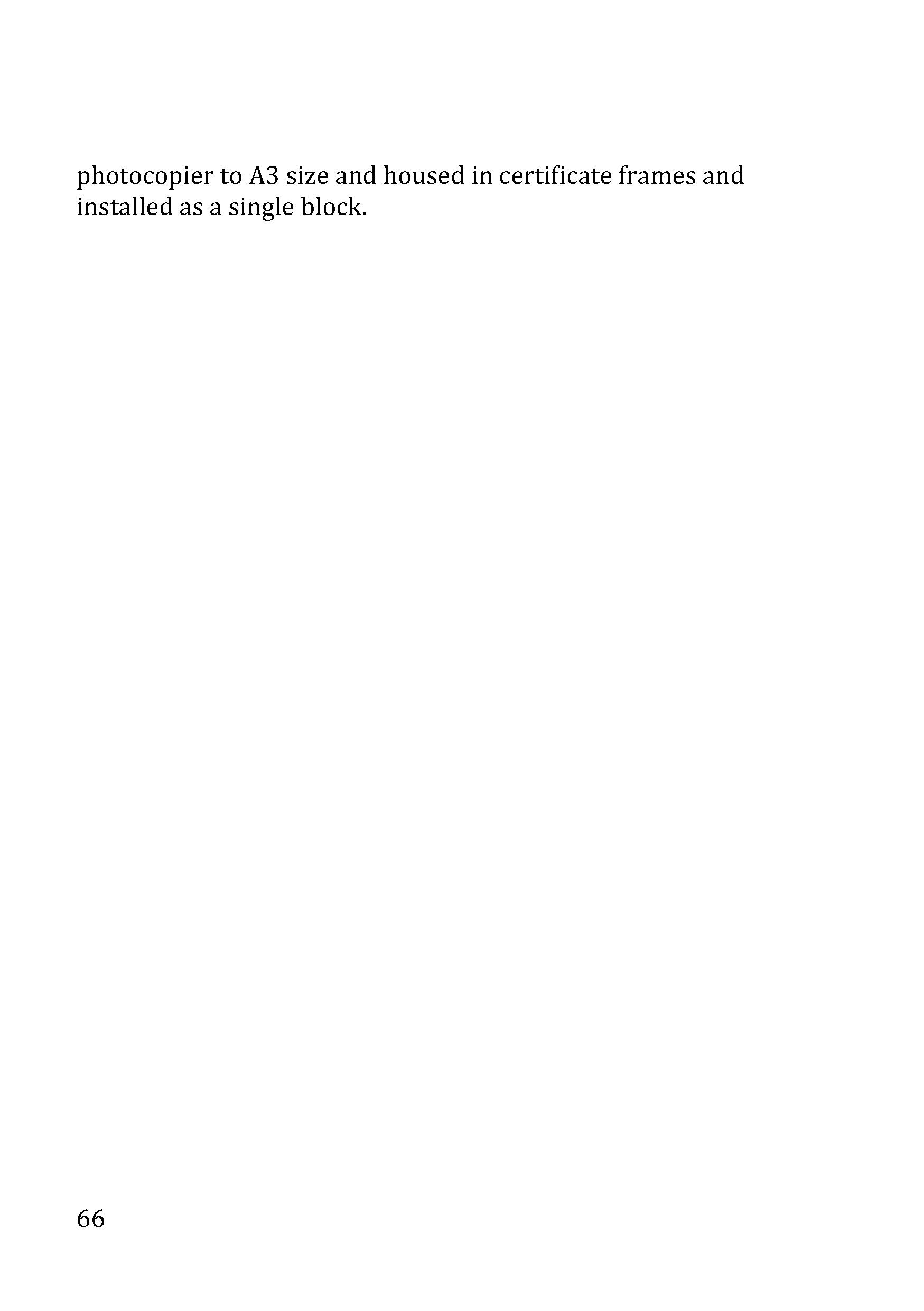

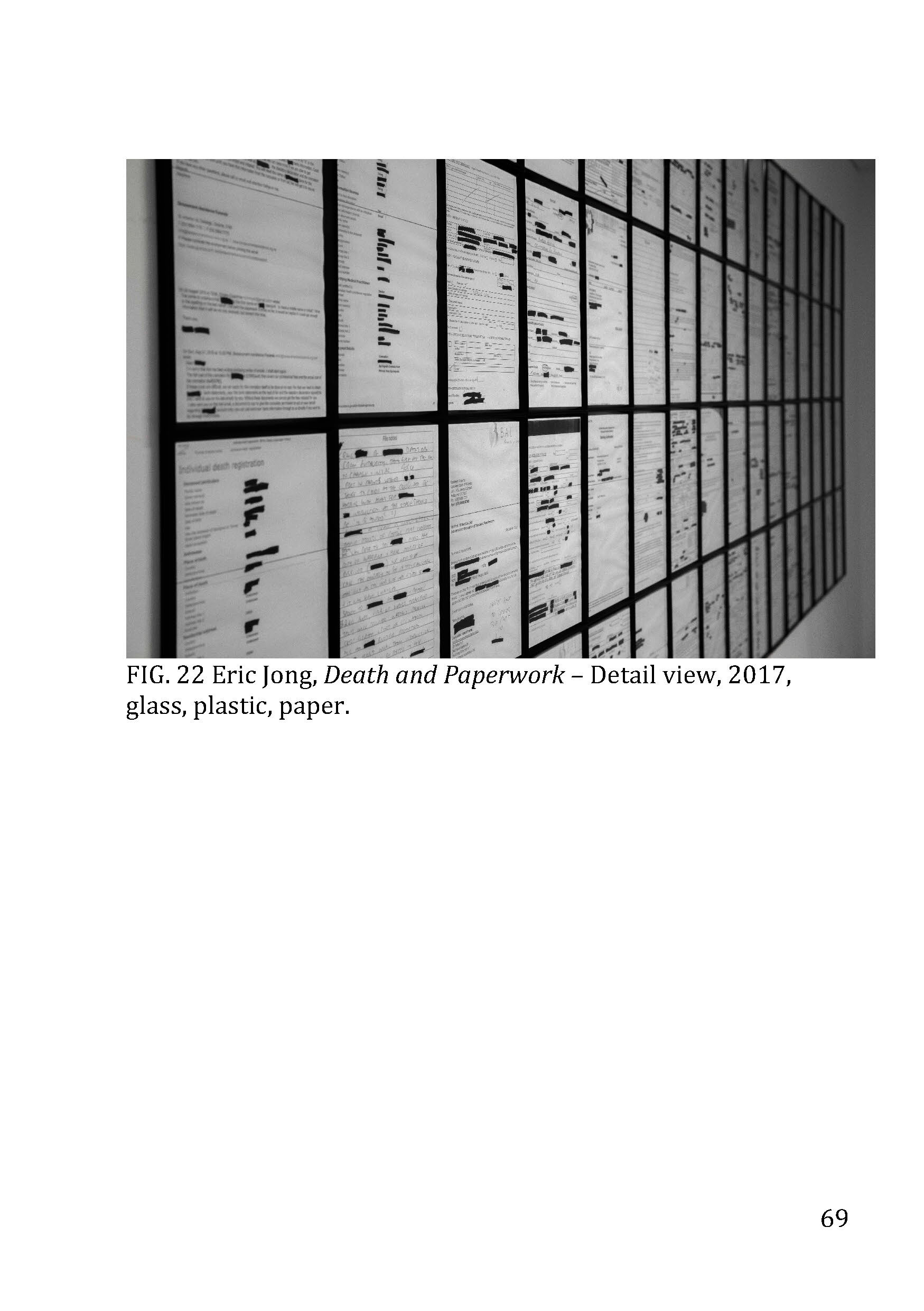

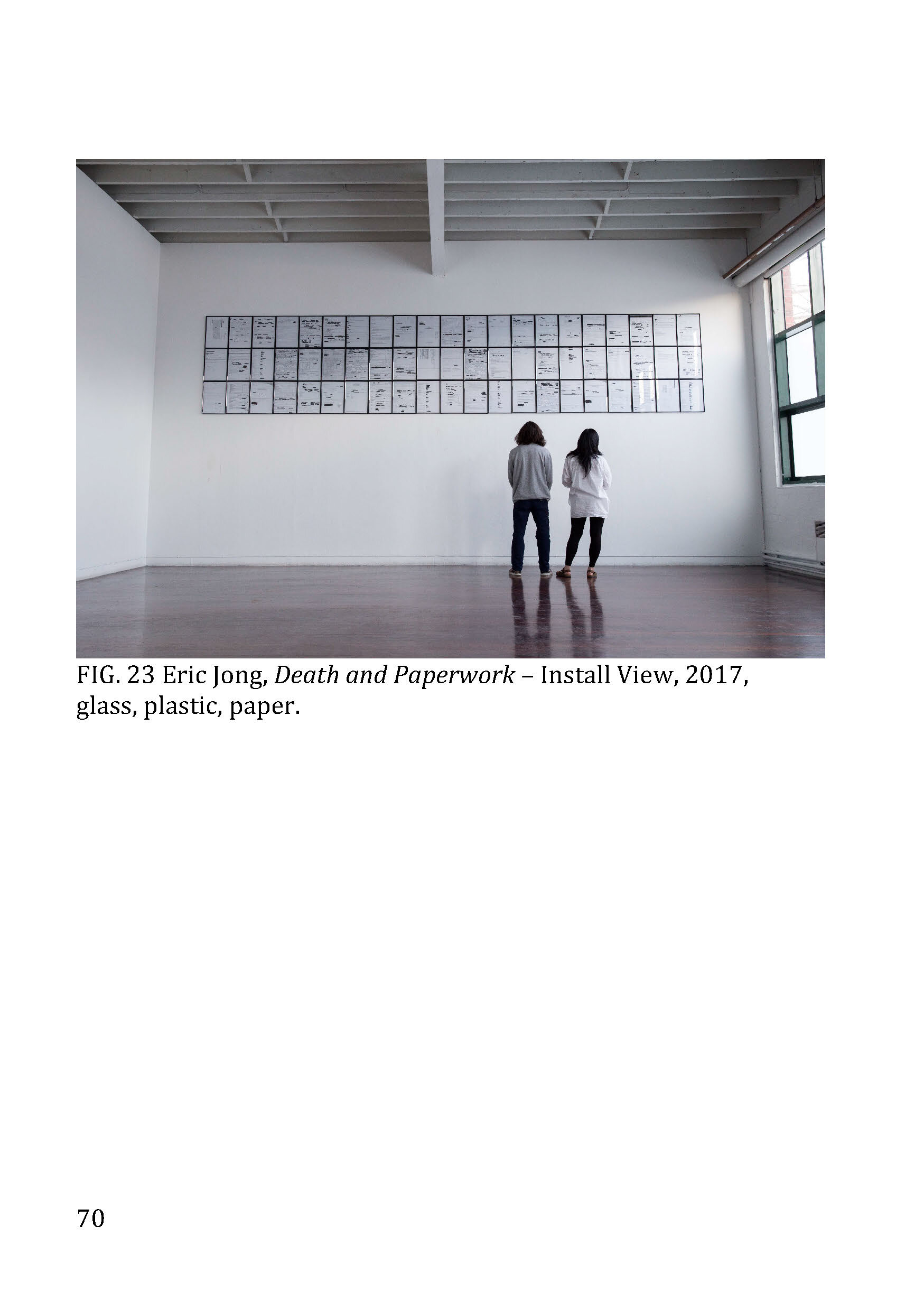

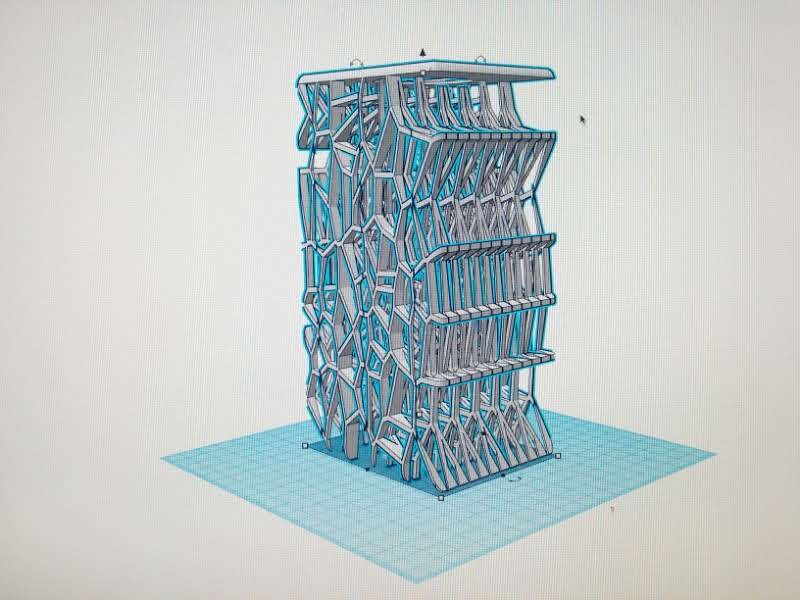

Death and Paperwork was a pivotal output from this research project and was produced by gathering masses of paperwork produced by Bereavement Assistance Limited as a means to reveal some of the bureaucracy that impacts us not just in life, but also in death. With all personal information redacted, the 65 A3 certificate framed works offer an unemotional audit and absence. In this act of presenting these documents as a form of memorial, Death and Paperwork draws attention to the state mechanisms for the administration and organisation of death, with a clinical distance from what it is to consider the memory and legacy of those who have passed.

Death and Paperwork was the most significant work that was produced during this research and was exhibited at the Margret Lawrence Gallery, receiving the Rodger Davies award. It was later exhibited as part of the Melbourne International Arts Festival in HOPE DIES LAST: ART AT THE END OF OPTIMISM at Gertrude Contemporary, where I was also invited to participate in a panel discussion for the public program.

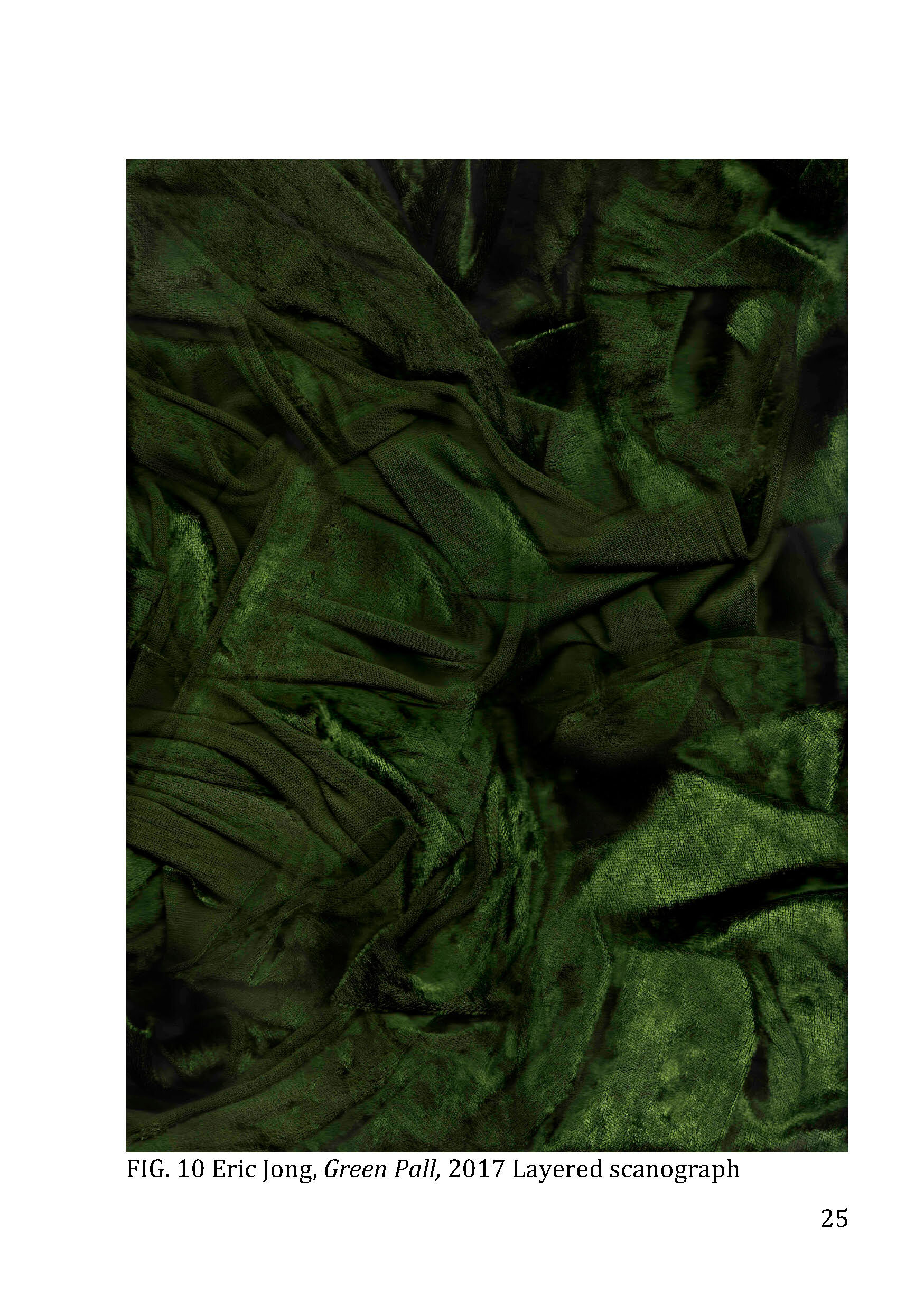

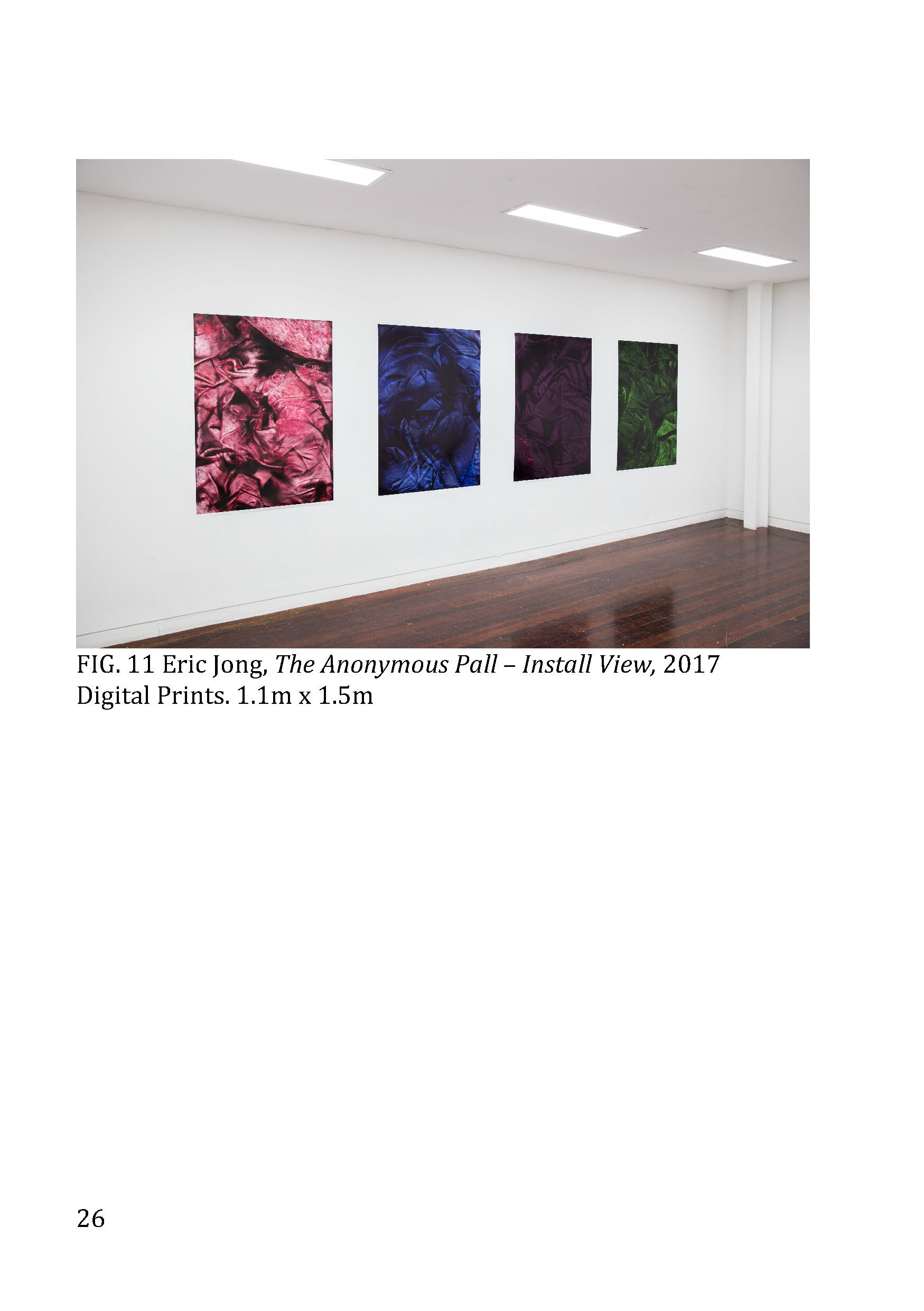

THE ANONYMOUS PALL: COFFIN CLOAKS OF DESTITUTE FUNERALS

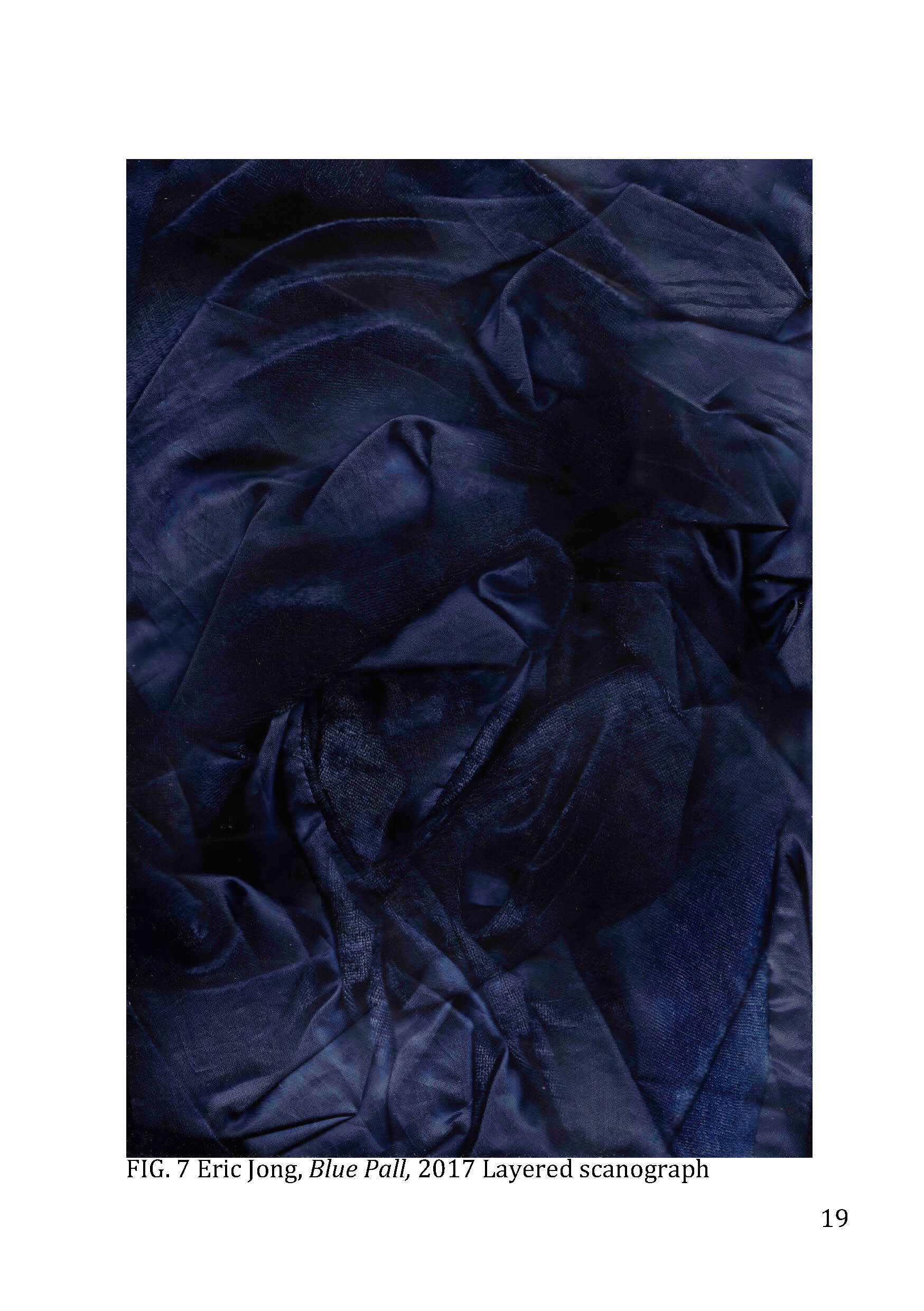

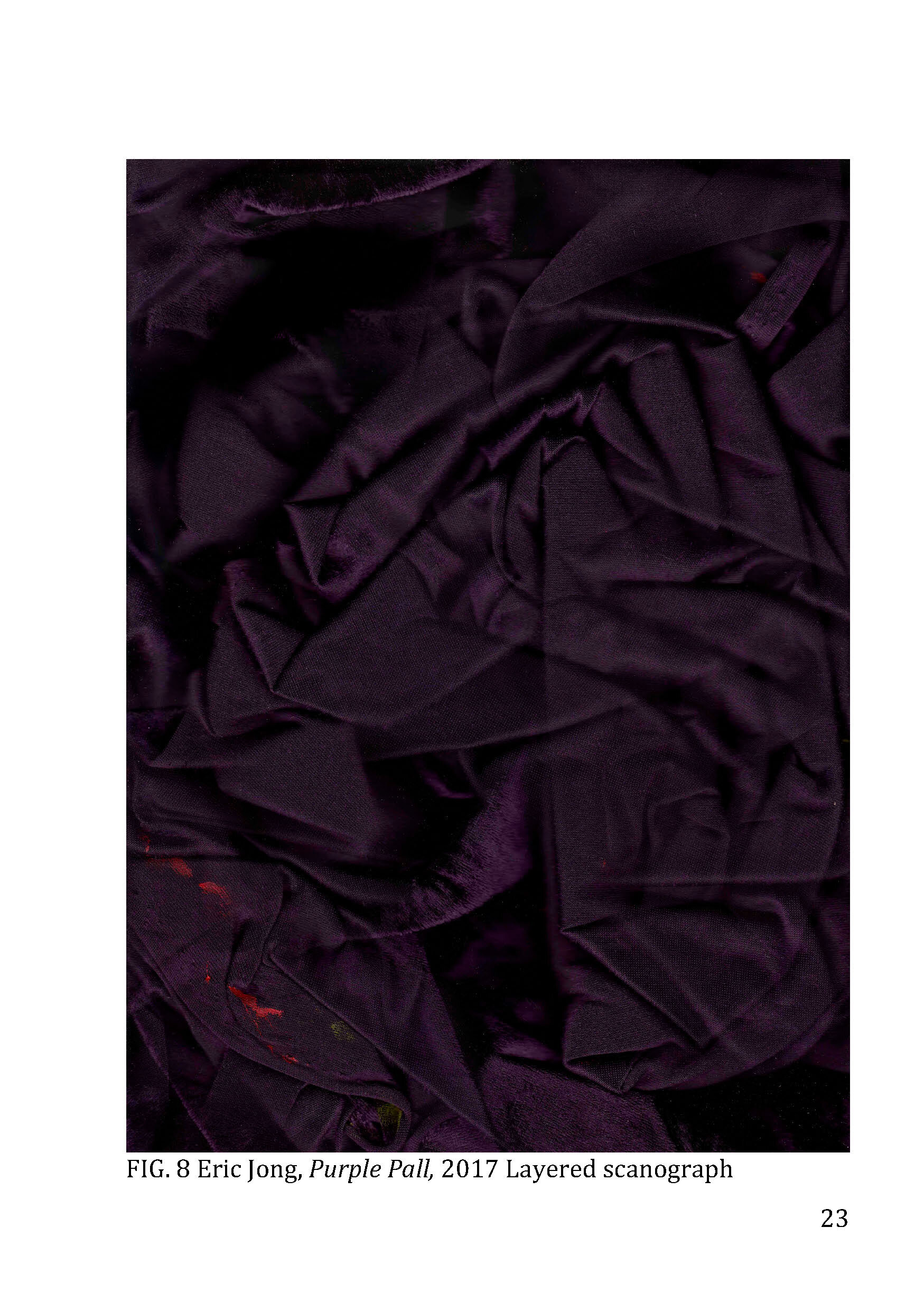

In the heraldic tradition, the pall stands out as a powerful feature of funeral ritual. A pall of the middle ages was a brightly coloured and expensively embroidered cloth heavy with the symbols of class and standing. They acted as a final vestment for the deceased, a final statement of position and status.

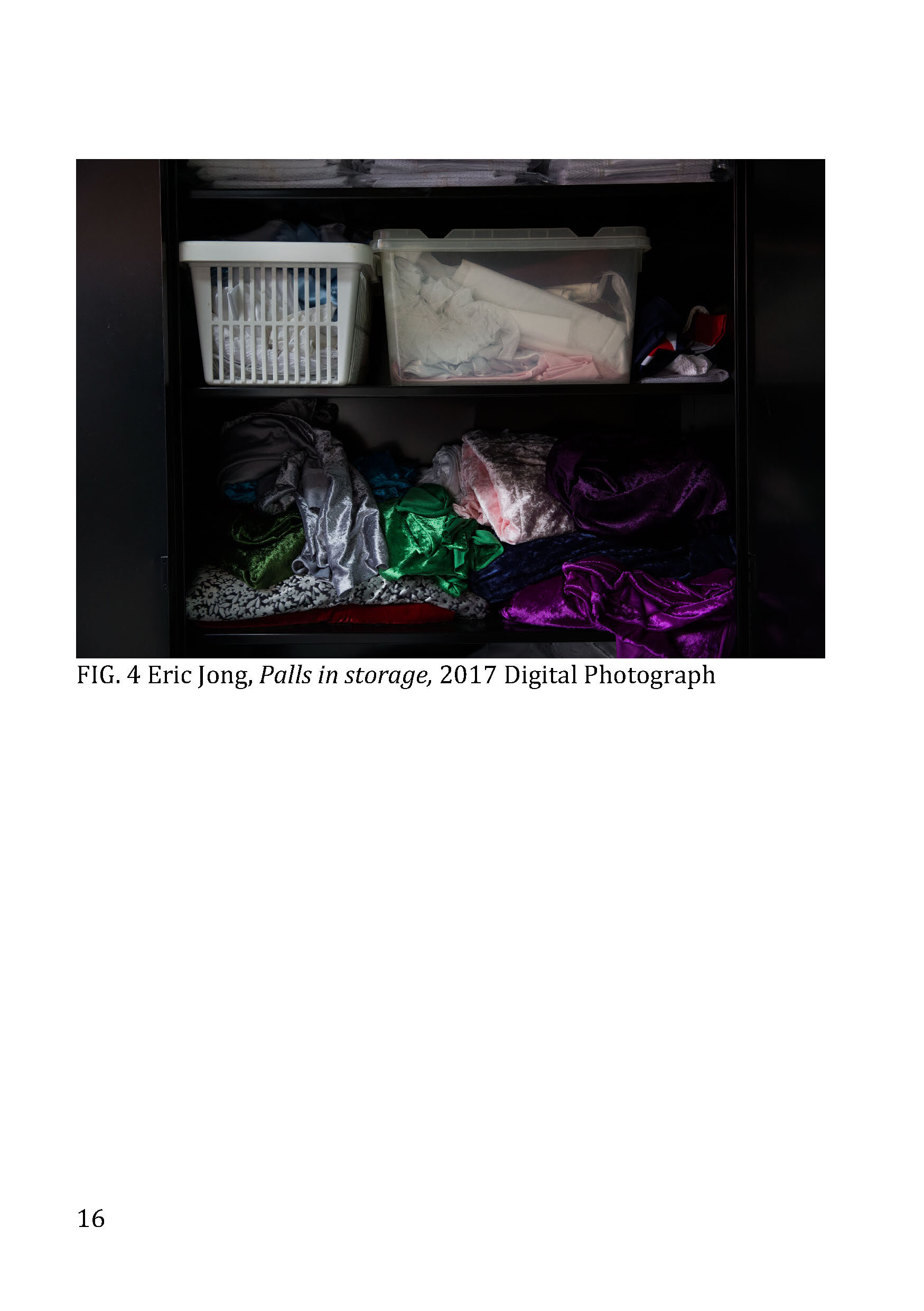

In a sense the palls that are used at Bereavement Assistance Limited still hold true to this power and legacy, but have found an inverted use in destitute funerals. Kept in a cupboard in the garage between stacks of coffins and the mortuary. These long bolts of crushed velvet are used to provide dignity to the deceased by covering the cheapness of the coffins of destitute funerals. Where once a coat of arms would appear instead are the marks of repetitive use, wear and tear, flecks of paint and loose stitching.

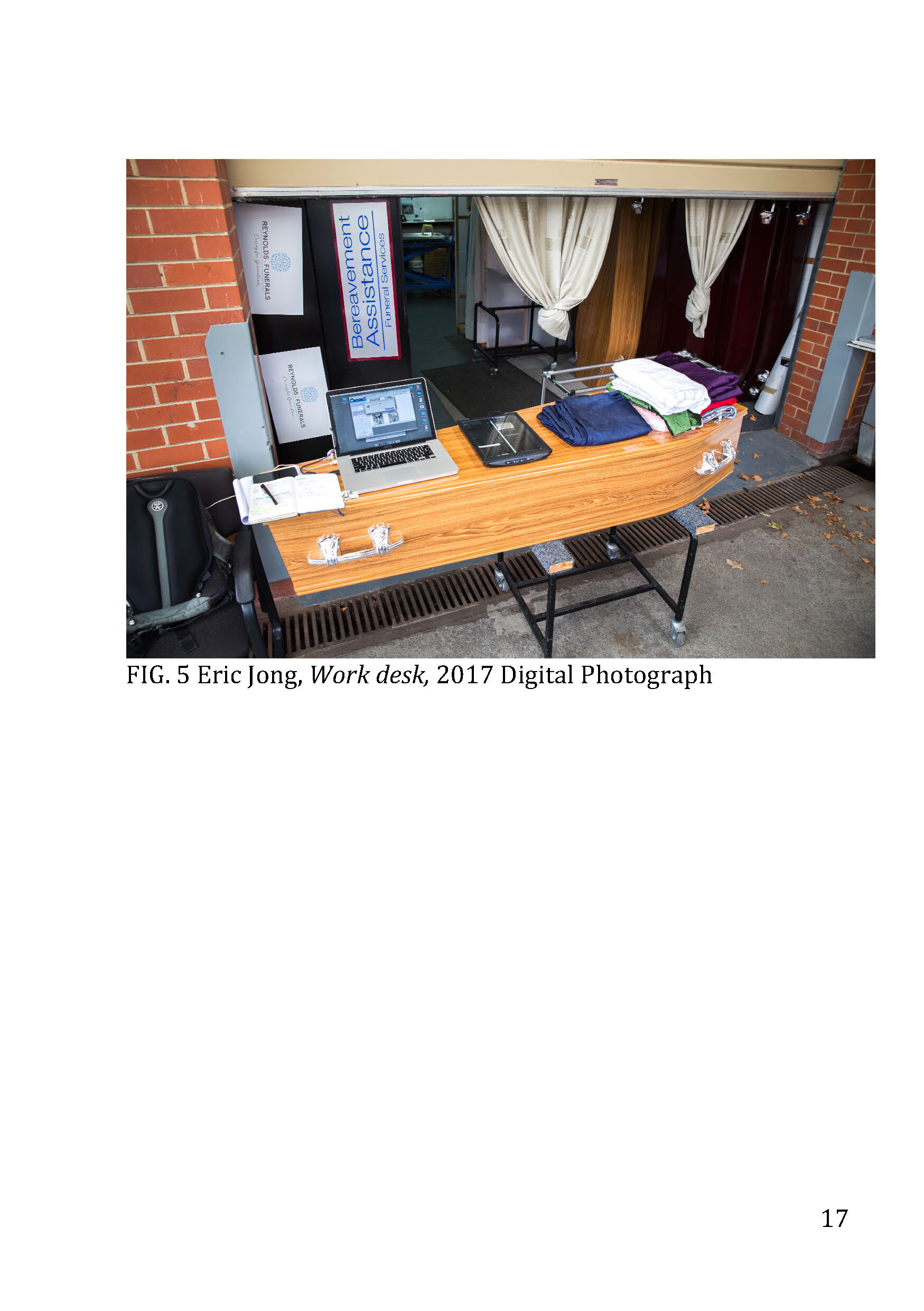

In response to being shown these palls at Bereavement Assistance Limited, and in light of my research into heraldic funerals, I created multi layered scans of the cloths, making the details of each cloth visible and printed them to a human scale.The staff at Bereavement Assistance Limited were kind enough to set me up on a working ‘desk’ for the scans.